In the 5000 years of recorded human history, there have been less than 300 years without war. In the last century alone, we have killed more of our fellow humans in warfare than in all previous recorded history. Yet even as we mourn the tragic losses of past conflicts, we earnestly prepare for the next one. Already in the 21st century, nations have spent ten times more money on their armed forces than on aid to poorer countries.

The question is why? Why do we humans--remarkable social animals with extraordinary intelligence--deliberately and systematically kill other members of our own species? Is war an immutable legacy of our primitive origins--leaving no hope for a peaceful world? Or is it a learned behavior, fostered by misguided societies, and therefore capable of change?

The Riddle of War is a feature-length documentary film that will take us on a rigorous journey in search of answers. We’ll meet primatologists in Africa, archaeologists in the Holy Land, anthropologists in the Amazon. And we’ll tell the compelling personal stories of warriors and pacifists alike. We’ll also feature commentary from researchers, writers and activists such as Jane Goodall, Sebastian Junger, Jon Krakauer, Nicholas Kristof, Tim O’Brien, Aun San Suu Kyi and Malala Yousafzai.

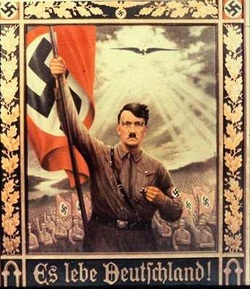

The Riddle of War will be a visceral, visual experience bringing rich archival imagery to life through animation, CGI and motion graphics. The film will feature a compelling original score by composer Curtis Bryant.

The documentary has no agenda but to seek an honest understanding of why we wage war on each other. Our hope is that in solving the riddle war we can also solve the riddle of peace: Is a world without war even possible?

The question is why? Why do we humans--remarkable social animals with extraordinary intelligence--deliberately and systematically kill other members of our own species? Is war an immutable legacy of our primitive origins--leaving no hope for a peaceful world? Or is it a learned behavior, fostered by misguided societies, and therefore capable of change?

The Riddle of War is a feature-length documentary film that will take us on a rigorous journey in search of answers. We’ll meet primatologists in Africa, archaeologists in the Holy Land, anthropologists in the Amazon. And we’ll tell the compelling personal stories of warriors and pacifists alike. We’ll also feature commentary from researchers, writers and activists such as Jane Goodall, Sebastian Junger, Jon Krakauer, Nicholas Kristof, Tim O’Brien, Aun San Suu Kyi and Malala Yousafzai.

The Riddle of War will be a visceral, visual experience bringing rich archival imagery to life through animation, CGI and motion graphics. The film will feature a compelling original score by composer Curtis Bryant.

The documentary has no agenda but to seek an honest understanding of why we wage war on each other. Our hope is that in solving the riddle war we can also solve the riddle of peace: Is a world without war even possible?

In Part I, “The Noble Savage,” we’ll explore the question of nature versus nurture. Was life in our distant past more peaceful, and war a rare occurrence?

Or is there an innate propensity to violence in humans that is part of our genetic makeup? Early human beings, wrote Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century, were “noble savages and strangers to war.” Humans wandered a vast fertile landscape in small bands, and encounters with fellow humans were rare and most likely amicable. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes, on the other hand, believed that early man faced the continual prospect of violent death at the hands of others. It was a life that was “nasty, brutish and short.” To Hobbes, the violent impulses of man could only be controlled by a strong government. Only civilization offered the promise of a peaceful existence.

But what do researchers now believe?

Or is there an innate propensity to violence in humans that is part of our genetic makeup? Early human beings, wrote Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the 18th century, were “noble savages and strangers to war.” Humans wandered a vast fertile landscape in small bands, and encounters with fellow humans were rare and most likely amicable. The philosopher Thomas Hobbes, on the other hand, believed that early man faced the continual prospect of violent death at the hands of others. It was a life that was “nasty, brutish and short.” To Hobbes, the violent impulses of man could only be controlled by a strong government. Only civilization offered the promise of a peaceful existence.

But what do researchers now believe?

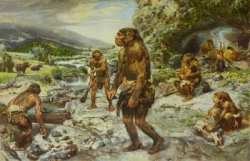

Chimpanzees—with which we share 98.7% of our DNA—were once thought to be a peaceful, cooperative species--which implied that early man too was nonviolent. Then in the 1960s, biologist Jane Goodall witnessed brutal battles over territory and sexual partners, which cast doubt on our own pacifist origins. Ancient rock drawings depicting warriors in combat were discovered, as were prehistoric gravesites of men, women and children who had met violent ends. And then there was the Iceman, a corpse from 3300 BC found frozen in the Alps in 1991, with an arrowhead buried in his back and the blood of four others on his clothes and weapons.

Even among primitive tribes today in New Guinea and the Amazon anthropologists have witnessed intermittent warfare. The evidence seems to indicate that group violence has been part of the human experience since the beginning.

But other experts challenge these findings. Some argue that violent encounters among chimps are actually rare. They point to the peaceful nature of our other close relative, the bonobo chimp, a cooperative species that eschews violence. Paleontologists examining ancient grave sites say the evidence that the wounds were incurred in battle is not definitive. And as for today’s warring tribes, there are anthropologists who believe the battles are more theater than combat.

And so the debate continues. But perhaps we are looking for answers in the wrong places. Perhaps the answers lie not in the jungles of Africa or in ancient grave sites or among primitive tribes today. Perhaps we should simply be looking in the mirror - at man at war today – and the roots of our “civilized” warfare.

But other experts challenge these findings. Some argue that violent encounters among chimps are actually rare. They point to the peaceful nature of our other close relative, the bonobo chimp, a cooperative species that eschews violence. Paleontologists examining ancient grave sites say the evidence that the wounds were incurred in battle is not definitive. And as for today’s warring tribes, there are anthropologists who believe the battles are more theater than combat.

And so the debate continues. But perhaps we are looking for answers in the wrong places. Perhaps the answers lie not in the jungles of Africa or in ancient grave sites or among primitive tribes today. Perhaps we should simply be looking in the mirror - at man at war today – and the roots of our “civilized” warfare.

In Part II, “The Path to War,” we’ll examine war in civilization. Warfare in early societies arose over control of the great rivers for transportation and irrigation, over boundary disputes, over resources such as timber, salt and metals. These wars were fought on a scale unimaginable to early humans. War as we know it had arrived and has remained virtually unchanged for more than 5000 years.

One can understand, the group violence of primitive man--if it indeed occurred. The potential rewards of battle were personal, immediate and evident – a water hole, food stores, a sexual partner. But in wars waged by societies, the spoils of war go not to the warrior and his family but to an abstract entity called the state. Yet the risks of death in battle are just as great if not greater. How do societies motivate individuals to not only risk their own lives but to take the lives of others?

One can understand, the group violence of primitive man--if it indeed occurred. The potential rewards of battle were personal, immediate and evident – a water hole, food stores, a sexual partner. But in wars waged by societies, the spoils of war go not to the warrior and his family but to an abstract entity called the state. Yet the risks of death in battle are just as great if not greater. How do societies motivate individuals to not only risk their own lives but to take the lives of others?

We’ll explore the roles of patriotism, religion and the “Just Cause” in promoting war. We’ll learn how states dehumanize the enemy to make killing fellow humans more acceptable. And further, how war is portrayed as not only essential but beneficial to society.

And yet history has shown that all parties engaged in warfare—victors and vanquished alike--endure catastrophic human and economic losses. If war is so beneficial to society, how could this be so?

War is also portrayed as important for building character: the Noble Warrior. But if this is true, why do those who experience combat suffer so on returning from battle? Alcohol and drug abuse, failed marriages and suicides—if anything, their lives are shattered. We’ll interview veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

And what we’ll discover is somewhat surprising. Much of their emotional trauma comes not from having risked their own lives but from taking the lives of others. It takes extraordinary physical and psychological coercion—beginning in boot camp—to induce men to kill their fellow humans. If war is the natural state of man, if war is part of our genetic inheritance, how could this be so?

In Part III, “The Riddle of Peace,” we’ll explore the prospects of creating a peaceful world.

We’ll meet members of a Mennonite sect in Belize whose forebears have been exiled from many countries over the centuries—all for their refusal to participate in war. And we’ll learn how pacifists have been persecuted throughout history.

This is paradoxical. For it is not our capacity for war that has raised humankind above other creatures on earth but our capacity for empathy, mutual aid and cooperation.

The human species is not particularly strong or fast or agile. But as a cooperative group we have proved indomitable.

And today—despite the violence in certain areas of the world—99% of humanity is living in peace. We compete for food, for shelter, for families, yes, but—like the Mennonites of Belize—we secure these things without resorting to killing each other. For all the distant thunder of war, our lives are filled with peaceful activities.

Since World War II, Europeans have enjoyed the longest stretch of peace in more than 2000 years. Interstate belligerence has all but disappeared in the Western Hemisphere. This suggests that a world composed of free and democratic states could be a peaceful one. Today in trouble spots from Pakistan to Palestine, a new generation of activists is working hard to achieve peaceful ends through peaceful means. People living today are less likely to die in wars than in any time in recorded human history. And this gives us reason for hope.

We have much work to do. Without the concerted efforts by the “haves” to help meet the basic human needs of the “have-nots,” the poor may still resort to group violence to obtain what they need to survive. The aggressive tendencies of young males—exploited by nations at war--can be channeled toward healthier goals. And, above all, the continued empowerment of women can go a long way towards setting social agendas for peace.

War remains the beast in restless sleep. We must watch for signs of its stirring: the coveting of other countries’ resources, the trumpeting of the Just Cause, the appeal to patriotic or religious identities, the demonizing of the enemy, the ennobling of war itself.

But if Rousseau’s idyllic image of the noble savage is a myth, so too is Hobbes’ grim conclusion that every man is the enemy of every man.

And therein lies the answer to the Riddle. The capability for war may lie deep within us. But not the inclination. War chooses us, we do not choose war. Knowing this, we can end the scourge of war – perhaps forever.

And yet history has shown that all parties engaged in warfare—victors and vanquished alike--endure catastrophic human and economic losses. If war is so beneficial to society, how could this be so?

War is also portrayed as important for building character: the Noble Warrior. But if this is true, why do those who experience combat suffer so on returning from battle? Alcohol and drug abuse, failed marriages and suicides—if anything, their lives are shattered. We’ll interview veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder.

And what we’ll discover is somewhat surprising. Much of their emotional trauma comes not from having risked their own lives but from taking the lives of others. It takes extraordinary physical and psychological coercion—beginning in boot camp—to induce men to kill their fellow humans. If war is the natural state of man, if war is part of our genetic inheritance, how could this be so?

In Part III, “The Riddle of Peace,” we’ll explore the prospects of creating a peaceful world.

We’ll meet members of a Mennonite sect in Belize whose forebears have been exiled from many countries over the centuries—all for their refusal to participate in war. And we’ll learn how pacifists have been persecuted throughout history.

This is paradoxical. For it is not our capacity for war that has raised humankind above other creatures on earth but our capacity for empathy, mutual aid and cooperation.

The human species is not particularly strong or fast or agile. But as a cooperative group we have proved indomitable.

And today—despite the violence in certain areas of the world—99% of humanity is living in peace. We compete for food, for shelter, for families, yes, but—like the Mennonites of Belize—we secure these things without resorting to killing each other. For all the distant thunder of war, our lives are filled with peaceful activities.

Since World War II, Europeans have enjoyed the longest stretch of peace in more than 2000 years. Interstate belligerence has all but disappeared in the Western Hemisphere. This suggests that a world composed of free and democratic states could be a peaceful one. Today in trouble spots from Pakistan to Palestine, a new generation of activists is working hard to achieve peaceful ends through peaceful means. People living today are less likely to die in wars than in any time in recorded human history. And this gives us reason for hope.

We have much work to do. Without the concerted efforts by the “haves” to help meet the basic human needs of the “have-nots,” the poor may still resort to group violence to obtain what they need to survive. The aggressive tendencies of young males—exploited by nations at war--can be channeled toward healthier goals. And, above all, the continued empowerment of women can go a long way towards setting social agendas for peace.

War remains the beast in restless sleep. We must watch for signs of its stirring: the coveting of other countries’ resources, the trumpeting of the Just Cause, the appeal to patriotic or religious identities, the demonizing of the enemy, the ennobling of war itself.

But if Rousseau’s idyllic image of the noble savage is a myth, so too is Hobbes’ grim conclusion that every man is the enemy of every man.

And therein lies the answer to the Riddle. The capability for war may lie deep within us. But not the inclination. War chooses us, we do not choose war. Knowing this, we can end the scourge of war – perhaps forever.